127 Hours (2010)

Movie rating: 9/10

What lengths would you go to in order to stay alive? That’s the perennial question posed by Jigsaw to his victims in the Saw franchise. It’s also the central question of 127 Hours, which unlike Saw is based on a true story and stars James Franco as real-life canyoneer Aron Ralston, who found himself trapped by a boulder during a solo hike through Utah’s Bluejohn Canyon. 127 Hours is based on Ralston’s memoir Between a Rock and a Hard Place, which has now vaulted to the top of my list of books to read.

I’ve been meaning to see this movie for a long time, but somehow never got around to it until now. I first heard about Ralston way back in a post by blogger Maddox, originally written in 2003, on his site The Best Page in the Universe. This was one of those tiresome articles about today’s supposed lack of “real men” which nowadays would immediately bore me out of my skull, but back then could still consider amusing. Maddox included Ralston as among his examples of “real men”. The first paragraph is honestly as good a summary as any about the events depicted in 127 Hours. Spoiler alert for those of you unfamiliar with Ralston’s story:

If you're asking yourself "who the hell is Aron Ralston," you'd better step back and re-evaluate your life right now. Ralston, the living legend, was hiking up a cliff in southern Utah (probably to do something manly like take a leak off of it), when a giant boulder fell on him, pinning his arm against the ground. Most people would have just died, but did he surrender his life to a mere giant life-threatening boulder? Hell no. He just kept getting angrier and angrier until he finally CUT OFF HIS ARM WITH A DULL KNIFE. This after he literally chiseled away at the bone so he could snap his arm off and free himself from underneath the rock. Yes, you read that correctly, he cut off his own arm with a dull pocket knife.

That’s a hell of a story no matter how you slice it, no pun intended. You can understand why director Danny Boyle—who co-wrote the screenplay of 127 Hours with Simon Beaufoy—spent years wanting to make a film about Ralston’s horrendous experience. The story is a natural for a book, given that Ralston was alone for more than five days. Reading about the thoughts that were going through his head throughout this ordeal will make for compelling reading. But could this story translate as well to the silver screen? How do you sustain interest over a feature-length film with a character who spends most of their their screen time alone?

Happily, Boyle managed to pull it off. Of course, 127 Hours is by no means the first cinematic survival story about a single character in a confined space. In 2000 we had Cast Away with Tom Hanks trapped on a desert island. In 2010, the same year 127 Hours came out, we also had Buried starring Ryan Reynolds trapped in a coffin. Since then we’ve had the likes of Oxygen, the 2021 film in which Mélanie Laurent plays a woman trapped in a medical cryogenic unit who is running out of air. I admit, I’m a sucker for these kinds of movies. I like survival tales in general, but it’s a unique challenge for an actor to hold the audience’s attention practically by themselves for an entire film. Meanwhile, the ticking-clock element adds innate suspense as we wonder how the character will manage to escape. In a way, the appeal of these films is the same as that of legendary escape artists like Harry Houdini.

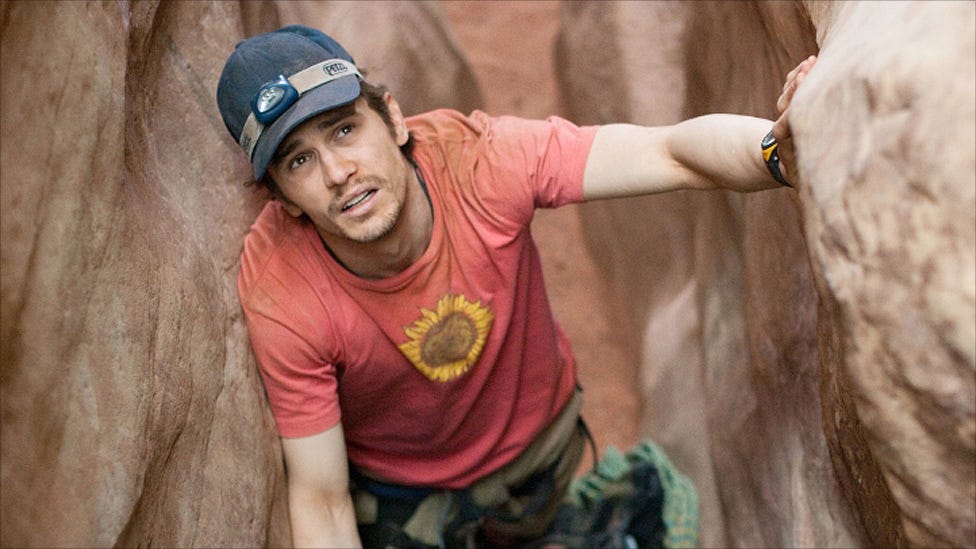

In 127 Hours, the actor that has to hold our attention is James Franco, which might be enough for some people to decide this is a movie they’d rather avoid. Franco has been persona non grata in Hollywood for the past few years since a string of sexual misconduct allegations and subsequent lawsuit. Whatever your thoughts on Franco as a person, he’s a talented actor and delivers a great performance here. At the beginning of the film Ralston is an affable solo adventurer who enjoys challenging himself physically and taking risks, yet doesn’t take all the precautions he should. He doesn’t tell anyone where he’s going when he heads out to the Canyonlands National Park. In an early scene, the full significance of which becomes apparent later on, we see his hand reaching into the cupboard for a Swiss Army knife that remains just out of reach before he gives up and leaves the apartment.

The most interesting emotional beats, of course, begin after Ralston becomes trapped by the boulder with his arm crushed against a rock wall. Franco perfectly conveys Ralston’s initial shock; his screaming frustration when he tries and fails to lift the rock; his efforts to stay calm and figure out a way to free himself; his growing desperation as his food and water run out; his descent into delirium, and finally his savage determination to do whatever is necessary to survive.

Boyle keeps things interesting in a variety of ways over the course of the running time. We see some impressive landscapes of the Utah desert canyons that convey the vast beauty of nature and underscore why a thrill-seeker like Ralston would do what he does. Early on Ralston meets two hikers, Kristi Moore (Kate Mara) and Megan McBride (Amber Tamblyn), and shows them an underground pool. These scenes are slightly fictionalized, since in real life Ralston simply showed them some basic climbing moves, but I can see why they changed it up for the movie. It offers more interesting visuals and a break from the otherwise monotonous rock and desert. Once Ralston is trapped, Boyle breaks things up with flashbacks and visions that give us more of a sense of who this man is and what drives him. It’s nothing terribly complex, but enough to flesh out the character a bit for the audience.

The occasional flashy split-screen editing feels unnecessary; I’m not quite sure what Boyle was going for when he used that at the beginning and end. In addition, the meaning of some of Ralston’s visions is not always clear. I’m thinking specifically of one where he envisions his future son, which gives him the drive to push forward, but I only realized that after reading the plot summary afterward.

Overall, though, this movie gave me pretty much what I expected, in a good way. Even though I knew what it was building up to, Boyle does an excellent job of escalating tension, and the climactic amputation is difficult to watch. At the end we see the real Aron Ralston, who continues to be an avid climber—albeit one who always makes sure to let people know exactly where’s he going when he heads out. Smart man. Dialectically, this film is a powerful reminder of how it’s through our mistakes that we learn wisdom. Some of those mistakes are more painful than others.