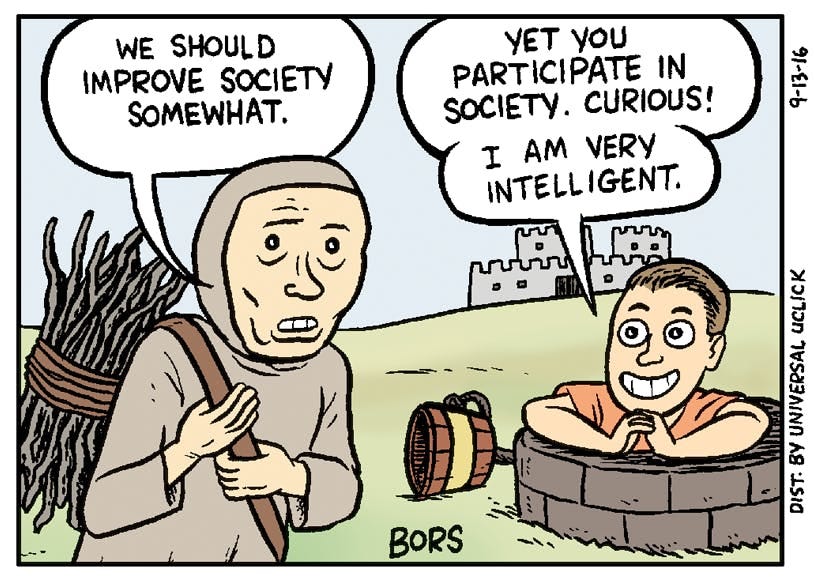

Does Pointing Out Hypocrisy Change Anything?

The assassination of far-right influencer Charlie Kirk has prompted a wave of propaganda in the capitalist media sanitizing his legacy and portraying the late white nationalist—who created a McCarthyist watchlist to encourage harassment and intimidation of university professors whose opinions he disagreed with—as a champion of “free speech”.

Naturally, many have pointed out the hypocrisy of Kirk and other reactionaries who act in ways diametrically opposed to the views they claim to hold. Detailing the hypocritical behaviour of the right is a never-ending task. In recent years there has been no more vivid case study of such hypocrisy than Donald Trump. Just to name a few examples: Trump postures as an opponent of the “deep state”, but sends masked ICE agents in unmarked vans to abduct people off the street and disappear them. He claims to support free speech while ordering crackdowns on pro-Palestine demonstrations at colleges and universities. He professes to stand for family values but cheated on his wife with a porn actress, etc.

But does drawing attention to this hypocrisy change anything? Recent tweets garnered thousands of likes and retweets raising this question and answering it in the negative: “It really would be awesome if pointing out hypocrisy did anything,” one person said. Another argued, “Pointing out conservative hypocrisy doesn’t work for a very specific reason: Getting away with it is a power trip for them. You’re essentially helping them gloat. And they think it’s funny that you care enough to be upset.” A third said the point of calling out right-wing hypocrisy is to “demonstrate this hypocrisy to other onlookers” and to “create social friction against their views.”

Hypocrisy is complicated. A 2016 Guardian article noted that “people tend to react more strongly to hypocrisy when it includes criticism or negative judgement”, such as a politician who attacks gay rights while engaging in homosexual acts themselves. People also more quickly notice and criticize hypocrisy when it goes against their own beliefs. In general, humans have a self-serving bias towards being more forgiving of our own behaviour, or that of people we agree with.

Here’s the good news. Research over decades has consistently shown that pointing out hypocrisy can effect positive social and individual change. In the 1960s, psychologist Milton Rokeach found making people aware that their actions did not match their attitudes could convince them to participate in the civil rights movement.

Rokeach conducted an experiment in which college students were asked to rank how much they valued freedom and equality, and then reported how much they personally supported the civil rights movement. Some participants were randomly assigned to the “inconsistency condition”, in which the researcher pointed out that the majority of those taking part said they valued freedom over equality, yet did not actively back the fight for civil rights.

The study found that a year and a half later, 25.88% of participants in the inconsistency condition had joined or wrote supportive letters to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. By comparison, only 10.65% of participants in the control group did so. Reflecting on the experiment, Stanford University’s behavioural-science think tank SPARQ noted the role of cognitive dissonance, in which we experience discomfort at holding two fundamentally contradictory views or acting in a way that conflicts with our thoughts:

We tend to feel good about ourselves when our actions are consistent with our thoughts, but we tend to feel bad when what we do is inconsistent with what we think. Pointing out the dissonance between our actions and thoughts can cause us to feel disappointed in ourselves. To relieve this negative feeling, we may change our behavior so that it is consonant with our values, attitudes, beliefs, and other thoughts.

American psychologist Elliot Aronson conducted multiple studies that showed beneficial effects of cognitive dissonance and making people aware of their hypocrisy. In a paper published by the American Journal of Public Health in 1991, Aronson and fellow researchers Carrie Fried and Jeff Stone found pointing out hypocrisy could encourage safe sex.

Their study asked participants to each compose a short speech in which they advocated condom use during all sexual encounters, then to deliver it in front of a camera for what they were told would be a video shown to high school students as part of an AIDS prevention program. Before taping the speech, half the participants were reminded of past occasions when they had failed to use condoms. The study found participants who were made aware of their own hypocrisy expressed significantly greater intention to increase their use of condoms in the future.

In another paper published by the Journal of Applied Social Psychology in 1992, Aronson, Chris Ann Dickerson, Ruth Thibodeau and Dayna Miller reported on the results of a similar study involving water conversation.

Female student experiments, posing as members of a campus water conservation office at the University of California at Santa Cruz, approached female swimmers as they exited the pool area and asked if they could help out with a water conservation project. Some subjects, in a “mindful” group, were asked to respond to a survey in which they reported on their own water-conservation habits during showering. Unbeknownst to the participants, another female student experimenter in the shower room then timed how long the participants showered.

Results of the water-conservation experiment were similar to those of the experiment for condom use. The study found that subjects who were made aware of the dissonance between their support for water conservation and their actual behaviour made greater efforts to reduce their shower time.

The evidence, then, is clear: pointing out people’s hypocrisy does encourage them to change their behaviour. So why doesn’t it appear to have more impact when it comes to politics?

Some commentators have pointed to a lack of shame, arguing that it is futile to try and “shame the shameless”. While there’s some truth here, the Guardian article might offer more clues towards the answer: people tend to be more forgiving of themselves and those who share their views.

In that regard, the concept of framing is essential. Political scientist George Lakoff defines framing as “mental structures that shape the way we see the world.” An implication of this is that “to be accepted, the truth must fit people’s frames.” Lakoff applies this lens to U.S. bourgeois politics, which reduces all politics to a binary of “conservative” and “liberal”, but his basic ideas are very useful and relevant.

For example, Lakoff views what he calls “strict father morality” as the foundation of conservative ideology. Strict father morality is built around a few key assumptions: there will always be winners and losers; children are born to seek pleasure and have no sense of right, which must be drilled into them through punishment; good children work hard and become prosperous; and doing good is based on submitting to authority, following one’s self-interest and becoming self-reliant.

Lakoff contrasts strict father morality to the “nurturant parent morality”, which he says underpins the “progressive” mindset. Writer Joel Dignam summarizes the nurturant parent morality as follows:

In this model, the government should function like parents who nurture their children to achieve their full potential. Lakoff argues that “nurturance” boils down to empathy and responsibility. That is, the government should be genuinely concerned about the misfortune experienced by others, and it has a responsibility to address suffering and to promote the flourishing of its citizens.

With all this in mind, it becomes easier to understand why certain examples of pointing out what appears to be right-wing hypocrisy have little effect.

Let’s take the example of reactionaries claiming to be “pro-life” based on their opposition to abortion rights. These same people often support the death penalty and imperialist wars, and reflexively defend police killing unarmed people. On the surface, this might appear to be a clear-cut example of hypocrisy.

Someone who accepts the framing of strict father morality, however, might see no hypocrisy at all. In this framing, there is a sharp demarcation between aborted foetuses and people killed as the result of capital punishment, police violence, war, etc. The former have not committed any acts that would justify their lives ending, whereas the latter deserve the punishment of death due to their actions: they are criminals, terrorists, enemy combatants, etc.

Then there’s the fact that accusations of hypocrisy go both ways on the political spectrum. To use one of the most clichéd examples, reactionaries will often respond to criticism of capitalism by noting that the person making the criticism has an iPhone, or is making it on a computer. The fact that it is labour, not capitalism, that creates iPhones and computers falls on deaf ears if the person you’re talking to has accepted right-wing framing that anyone who criticizes capitalism is just a lazy welfare bum who wants everything for free.

When you have accusations of hypocrisy hurling in all directions, it becomes easier to ignore hypocritical behaviour. One can make the self-evident observation that no one is perfect. A 2018 article by Diane Winston for the Religion News Service, titled “How can Christians support Donald Trump?”, makes precisely this observation:

God uses imperfect messengers, evangelicals reasoned, and if King David — an adulterer who arranged to have his partner’s husband killed — could still accomplish great good, why not the 45th president?

So it was a realpolitik calculation that drove so many white evangelicals to the Trump-Pence ticket [in 2016]. It was also stoked by economic uncertainty, cultural anxiety and a sense of social marginalization that festered through the Obama years. They wanted an affirmation of their status, and Trump offered one.

Even with all these caveats in mind, I think it’s still worthwhile to call out the hypocrisy of the right—not on the basis that you will convince dyed-in-the-wool reactionaries to change their views, but rather to convince onlookers.

That’s the best way to approach arguments with strangers on the internet, which otherwise are a waste of time. Right-wing idiots can easily overlook their own hypocrisy, but third-party observers will feel differently. The studies of Rokeach and Aronson show how ordinary people—who, unlike Donald Trump and Charlie Kirk, don’t have a material interest in propagating a certain worldview or ideology—are more likely to change their own behaviour when they become aware of the gap between their own actions and what they profess to believe.

Under capitalism, our entire social system is hypocritical because it’s based on defending the interests of the ruling class. Consider televised political debates in which moderators demand of any left-wing politician who supporting programs to benefit workers and the poor, “How are you going to pay for it?” These same talking heads never ask that question when it comes to policies that benefit the capitalist class such as bailouts, increasing military spending, or cutting corporate taxes.

Morality, like everything else in class society, flows from class interests and cannot be separated from them. Official responses to individual hypocrisy—whether they are condemned or excused—depend entirely on whether that individual advances the interests of the ruling class. Democrat politicians and liberal media are currently falling over themselves to praise Charlie Kirk because they recognize that widespread anger against Kirk—who defended the capitalist system along with racism, misogyny, homophobia and transphobia—also threatens them.

The class struggle of workers to run society is also a struggle against the hypocrisy of bourgeois morality. Only by overthrowing capitalism and class society itself can we resolve this contradiction.