G.I. Blues (1960)

6/10

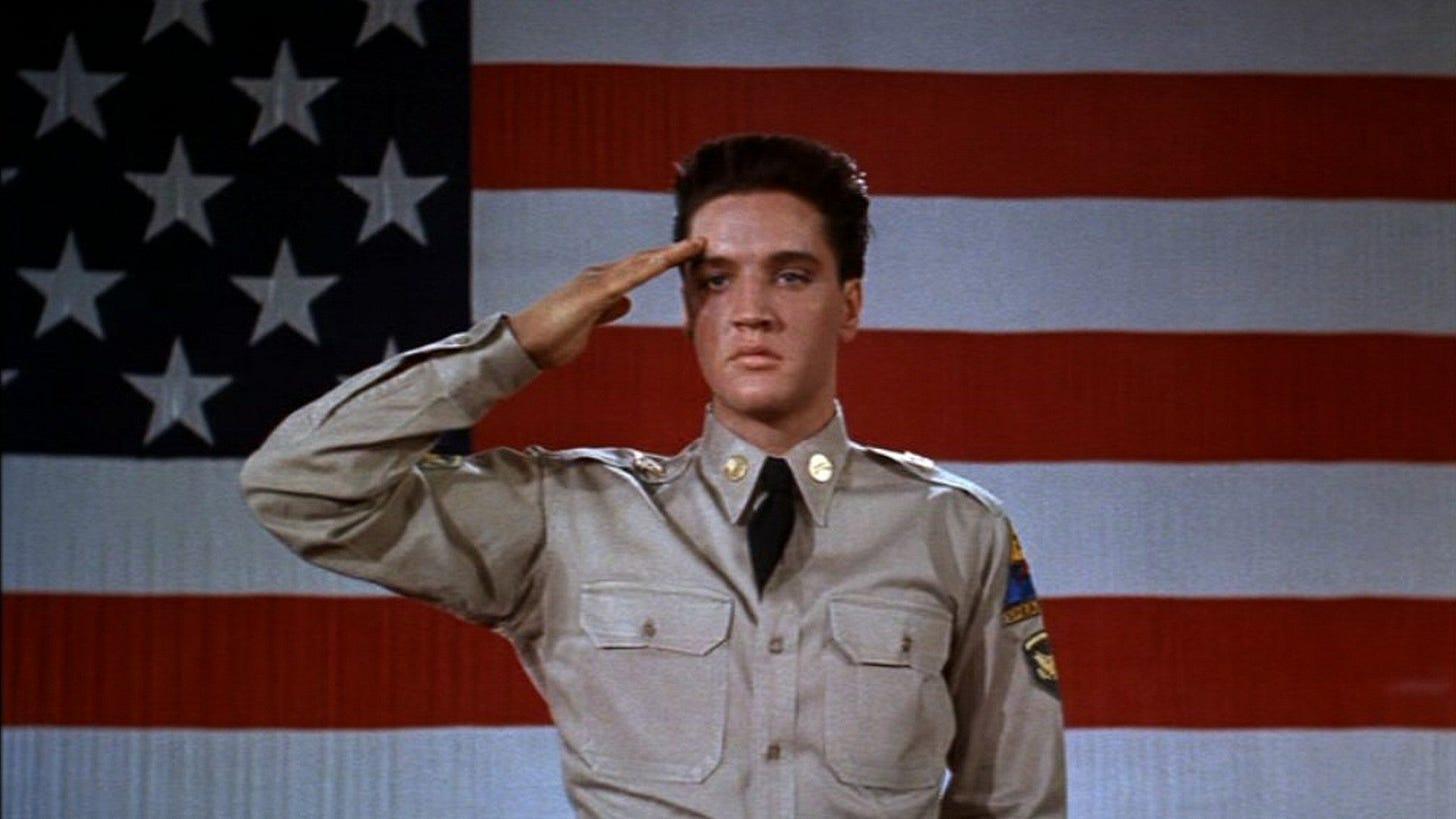

Elvis Presley’s first film after leaving the U.S. Army, G.I. Blues marked a turning point in his movie career. When he first entered Hollywood, Presley spoke earnestly about wanting to become a serious actor. But G.I. Blues, loosely inspired by his military service, was the first in what turned out to be a long line of vapid, interchangeable musical comedies that would define the King’s filmography, with Blue Hawaii solidifying the formula.

Presley plays Spec. 5 Tulsa McLean, a tank commander serving with the 3rd Armored Division in West Germany who sings with his band on the side and dreams of owning a nightclub in Oklahoma. Tulsa places a bet with his fellow soldiers that he can spend a night with Lili (Juliet Prowse), a club dancer at the Café Europa in Frankfurt. A predictable romance and various subplots ensue.

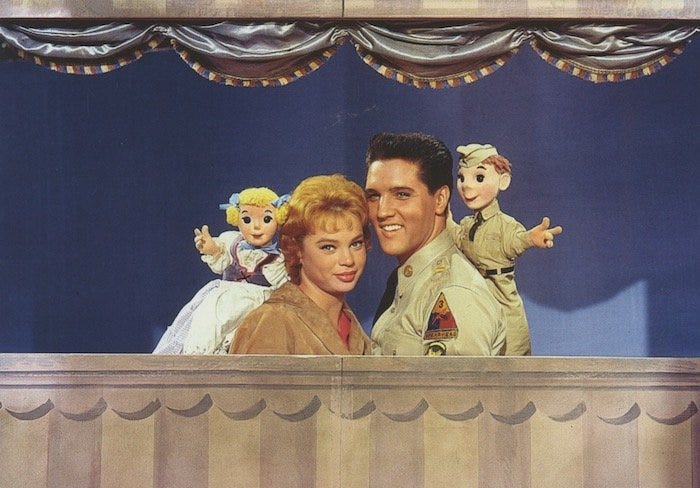

By itself, G.I. Blues is perfectly acceptable light entertainment. Within the larger context of Presley’s career, however, it represented the symbolic end of Elvis the ’50s rebel and his transformation into Elvis the clean-cut, all-American family entertainer. The hip-shaking rock ‘n’ roll icon was now singing songs to puppets and babies. Where before he appeared as a threat to the establishment, in G.I. Blues Elvis has become part of the establishment. Though there would be high points in Elvis’s early 1960s work both on record and celluloid, G.I. Blues started a slow artistic decline that only ended with the singer’s legendary ’68 Comeback Special.

I went into this film expecting low stakes, yet somehow they ended up being even lower. Tulsa’s fellow soldiers describe Lili as an ice queen and initially it seems like it will be a real challenge for him to “break down her defences”. It’s not. Lili is impressed by Tulsa as soon as he sings his first song because hey, this is a young Elvis Presley. It doesn’t take much cajoling before they’re on a date and Lili invites Tulsa back to her place.

The main appeal of Elvis movies is always the King himself and the songs he sings—the key variable being the quality of the material. Thankfully, G.I. Blues has enough good songs to make it an entertaining watch. “Pocketful of Rainbows” is one of my favourite Elvis songs and is used well to show the deepening affection between Elvis and Lili. “Shoppin’ Around” is a fun, playful rocker, “Doin’ the Best I Can” a fine ballad, and the title track greatly boosted by Elvis’s delivery.

Others fall into the category of novelty songs, with varying results. Take “Wooden Heart”. While it’s interesting to hear Elvis sing a German folk song, it’s the kind of number that likely never would have been recorded outside the context of the film. “Frankfort Special” is a watered-down “Mystery Train” with lyrics tailored to fit the plot. “Big Boots” is a lullaby that Elvis sings to a baby, with a title referring to the father’s nickname. “Didja’ Ever”, which closes the film, is just lame.

Beyond the music, the quality of Elvis movies depend on added-value elements such as the supporting cast and exotic locations. Prowse falls into the upper echelon of the King’s leading ladies, due partly to their chemistry together and partly to Prowse’s impressive dance routines. While Elvis has natural sex appeal and displays his natural charisma and playfulness, he is more restrained here post-army. Prowse’s risqué dance routines—which brought international press attention during filming of the movie Can-Can when Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev denounced them as immoral—occasionally threaten to steal the film.

G.I. Blues is well-made thanks to the reliable direction of Norman Taurog, in the first of his nine Presley films. The German setting offers an exotic location that has more personal resonance for me than those in most Elvis movies. I’ve long been something of a Germanophile, having been born on a Canadian military base in Lahr, West Germany and as a teenager lived for two years each in Hamburg and Berlin. Elvis once characterized many of his movies as “travelogues”, but there’s innate appeal in seeing this quintessential American icon interact with different cultures.

Where the film falls short is in the utter lack of real conflict or stakes, not to mention irritating side characters and subplots. Any obstacles in the romantic relationships are quickly and easily resolved. There’s a subplot involving a baby which frankly wears on the nerves due to the infant’s incessant crying, and which leads to the aforementioned lullaby. It’s not what I want to see in an Elvis film. Unfortunately, Elvis singing to children became a recurring element in many of his big-screen adventures. On the other hand, like most Elvis movies we also get the obligatory fistfight in the case of a good barroom brawl.

In the end, G.I. Blues is better than many of Elvis’s subsequent musical comedies, with higher production values and better songs. Where Presley often phoned in his performances for later films, the King’s visible enthusiasm in 1960 to be back in America singing and starring in movies helps elevate this film.