How the Franco-Prussian War Set the Stage for the First World War

The assertion above will come as no surprise to anyone with a basic knowledge of the history of Europe in the decades leading up to the Great Slaughter of 1914-1918. Nevertheless, I’ve gained a deeper understanding for precisely what that means after reading The Franco-Prussian War: The German Conquest of France in 1870-1871 by Geoffrey Wawro, a professor of strategic studies at the U.S. Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. Methodically laying out the background to the war and describing its major battles, Wawro shows the respective strengths and weaknesses of each side and how German forces led by the Prussians consistently took advantage of French missteps—and how poor leadership on the French side doomed the country to military defeat.

The key figures at the outbreak of the war were Napoleon III, emperor of the Second French Empire, who faced growing internal dissent and saw a war as a way to save his failing regime; and Otto von Bismarck, the conservative chancellor of the North German Confederation, who helped spark the war he saw as a way to unite the German states under Prussian leadership while managing to make France appear the aggressor. Bismarck dominated European affairs in the latter half of the 19th century and is famed for his droit diplomacy associated with the concept of Realpolitik, by which he sought to maintain peace and the balance of power in Europe after German unification in 1871.

In 1870, despite growing industrialization and a string of Prussian military victories in the Second Schleswig War and then in the Austro-Prussian War, Prussia was still considered something of a backwater and second-rate power compared to France—long the dominant country in continental Europe. Rival powers expected a French victory. The swift defeat of France and creation of the German Empire stunned contemporary observers. The resulting shockwaves laid the groundwork for developments in the next major European war, which became the First World War. Here are some of the biggest ways the results of the Franco-Prussian War shaped the cataclysm of 1914-18.

Adopting Prussian military methods

Established in 1814, the Prussian General Staff was the first full-time general staff in the world: a full-time body at the head of the Prussian military devoted to the continuous study of warfare and planning all manner of future mobilizations and military campaigns. The existence of this general staff—led for 30 years by chief of staff Hulmuth von Moltke the Elder, including during the Franco-Prussian War, —gave Prussia a distinct advantage in leadership compared to French generals, who under the Bonapartist regime tended to achieve their positions more due to background and connections than ability. The superior leadership of Prussian forces filtered down to the lower ranks: Prussian soldiers were better-educated than their French counterparts and encouraged to seize the initiative on the battlefield.

Another advantage the Prussian military had was its ability to draw on a much larger supply of manpower due to universal conscription. France preferred a model of long-term professional soldiers, recruiting fewer men but keeping them on for longer periods. The dominant view among French generals was that their men’s greater experience made them superior to Prussian conscripts. However, the portrait Wawro paints of French soldiers at the outbreak of war is one of an unfit army with extremely poor discipline:

In his anonymously published L’Armée Française en 1867, General Louis Trochu laid bare the flaws of the French system. French soldiers, who habitually reenlisted and soldiered into their fifties and sixties, were simply too old, too jaded, and too cynical. Plucked from their villages and families at a young age, the troupiers had become coarse and impenetrable in an all-male society. Despised by their officers and indifferently supplied even in their peace time barracks, they had become habitual scroungers or débrouillards, a practice that all too often crossed the line into thievery. Jean-Baptiste Montaudon, a French officer who had seen discipline collapse in the Franco-Austrian War of 1859 when thousands of French soldiers pretended to “lose” their units to scavenge or escape the fighting, called French soldiers “vermin” and “parasites".” Trochu called them “whoremongers” - “fricoteurs” - and pleaded for stricter discipline. An astonishing number of French soldiers in the 1860s were alcoholics who eased the boredom of garrison life with hard drinking. Because troopers took a dim view of drinking alone - a practice they called “acting Swiss” - individual tippling tended always to widen into a torrent. In this respect at least, republican sneers about the “corrupting life of the barracks” seem to have been on target. Trochu asserted that French soldiers literally drank the entire day, beginning with wine (un pauvre larme - “a little teardrop”), progressing to spirits (le café, le-pousse-café), climaxing with a gut-searing brandy (le tord-boyaux - “the gut-wringer”), and ending with la consolation, a sweet liquer that the French soldier sipped as he lay in his bunk contemplating the next day’s exertions. Far from imbuing the army with an ésprit de corps, the French system tended to destroy it, fresh-faced youngsters succumbing to the bad habits of their elders.

Contrast this to Wawro’s description of the Prussian military:

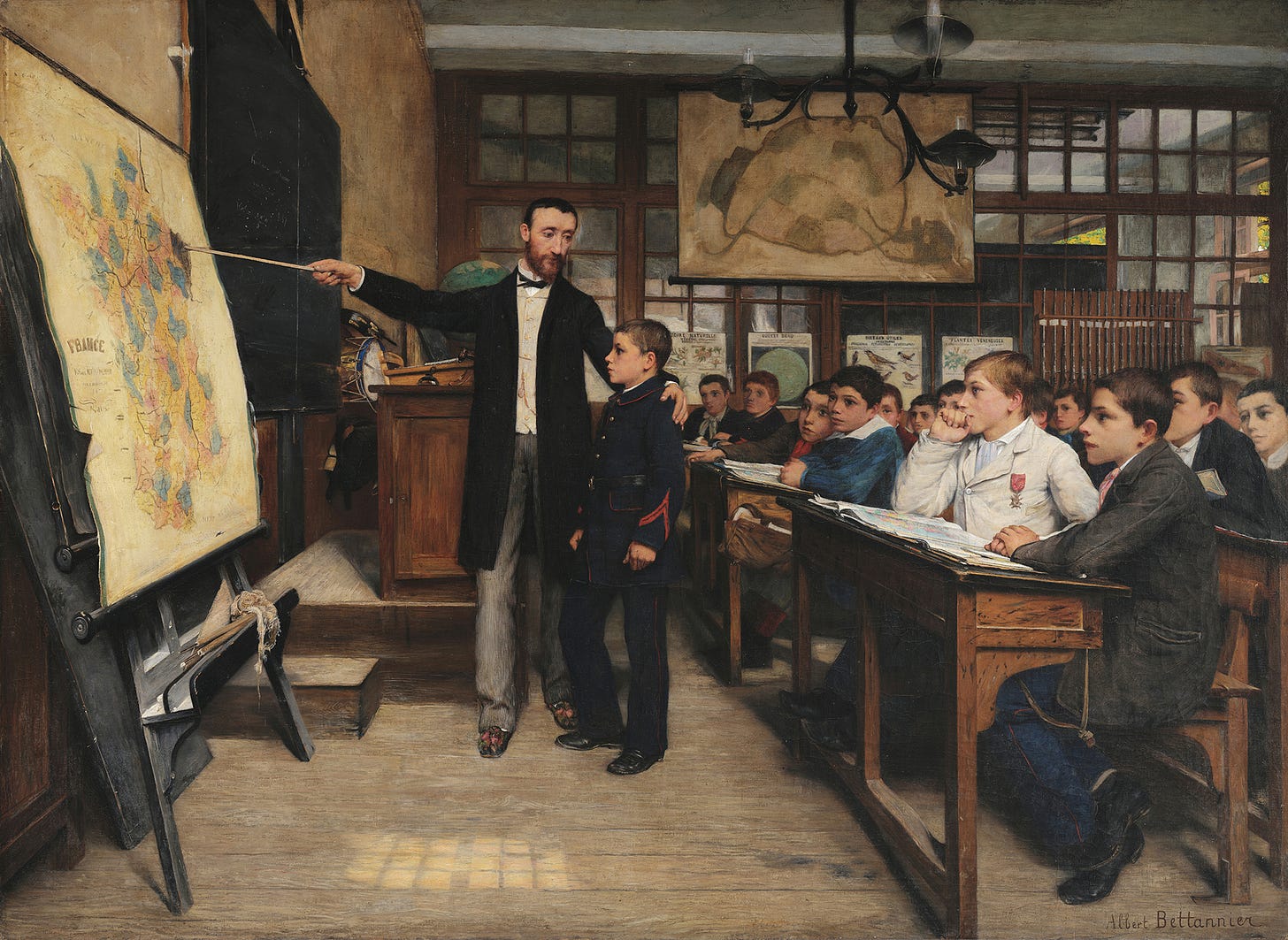

The impression made by the Prussian army was altogether different. Though the French disparaged the short-service Prussian force as an “army of lawyers and oculists” - pauvres bourgeois de 40 ans - the Prussians were actually extraordinarily fit, well trained, and disciplined. To begin with, all Prussian males were literate and numerate; they were the product of compulsory primary schools that were not adopted in France until the 1880s. They could be shown models, drawings, and maps, and involved in complex tactical exercises. Their three years of military service were so intense and well-organized that they had only to meet four or five times a year as reservists and none at all as Landwehr men to refresh their skills. Once conscripted, Prussians took more target practice than their peers in other armies, and practiced small-unit fighting in camp and in tutorials, where veterans described the pace and confusion of combat to green recruits. Their military education continued off the parade ground. Dienstliche Vorträge or “service lectures” echoes through the Prussian barracks after troop exercises. Fresh from the yard or obstacle course, still sweating from their fatigues, Prussian recruits were lectured by their NCOs, big, wooden men, who woodenly drove home the virtues of discipline, obedience, and order: “Der Soldat soll das Vaterland gegen äussere Feinde verteidigen, und die Ordnung im Innern beschützen” - “The soldier must defend the fatherland against external enemies and also uphold domestic order.” Indoctrination like this took root in young minds, yielding a ferocious discipline that would serve the Prussian army well in the harsh winter campaign of 1870-71.

While France was able to mobilize its armies more quickly in 1870, Prussia had much larger numbers of soldiers in all the major battles of the war. France’s only chance to gain the upper hand would have been to aggressively deploy its forces early on. But the curiously passive strategy of French generals—particularly François Achille Bazaine, commander of front-line forces including III Corps and the Army of the Rhine at Metz—meant this opportunity was thrown away at almost every turn. (Sadly, the passivity of its generals in the Franco-Prussian War led France to embrace the “cult of the offensive” and the idea that any material obstacles in warfare could be overcome with enough élan, leading to horrific casualties in World War I.)

In the wake of of the Franco-Prussian War, militaries everywhere sought to emulate the Prussian model. Wawro writes:

Armies that had begun to adopt Prussian methods after [the Austro-Prussian War in] 1866 accelerated the process after 1870. Universal conscription was introduced to swell the ranks, enable Moltkean “pocket battles,” and replace casualties that the Franco-Prussian War had generated in shocking quantities. General staffs were established or expanded. Professional military education, war games, and staff rides were introduced from Washington to Tokyo. Railways, telegraphs, medical arrangements, and logistics were given a very business-like emphasis in every war ministry. Although the cumulative result of these changes would be mutual slaughter, far worse than that inflicted by the rather devil-may-care French on the rigorous Prussians in 1870-71, that probability was not allowed to obstruct the march of progress.

The creation of mass armies by all the great powers meant future battles would be both larger in scale and longer in duration, as countries could draw on ever larger supplies of manpower through universal conscription. By 1914, as A.J.P. Taylor wrote in his seminal book The First World War: An Illustrated History, “These mass armies were too big to live off the country. They had to be fed from their homeland. In this way the very size which had been designed to bring victory made it impossible for the armies to win or even move.”

German unification alters balance of power

Since the Congress of Vienna in 1814-15 which set out the political order in Europe following the Napoleonic Wars, a certain balance of power had prevailed between the major European powers: Britain, France, Prussia, Austria, and Russia. The creation of a unified German nation-state led by Prussia shattered this balance. Rival powers feared that Germany, with its growing population, fast-developing industry, and military and economic power, would dominate Europe.

But Germany, despite its crushing victory over France, felt less secure than one might have imagined. Wawro describes how the changes wrought by the creation of the German Empire created a general feeling of anxiety among all the great powers:

The familiar landscape of five balanced great powers and a dozen biddable “middle states” had been shredded by the Prussian victories in 1866 and 1870-71. The opposition between Berlin’s anxiety - that France would rise again and a “revenge coalition” would unite against Germany - and the rest of Europe’s conviction that Germany had become colossal and threatening would generate burning friction in the decades ahead, and be a principal cause of World War I.

Revanchism in France

Meanwhile, in France, the harsh terms imposed by Prussia after the war created a culture of revanchism, a burning desire for revenge against Germany. Under the terms of the armistice, the Prussian Army held a victory parade in Paris, a humiliating sight for many Parisians. Bismark allowed a full withdrawal of Prussian forces only after France agreed to pay a 5-billion-franc war indemnity. But perhaps the worst affront for many French citizens was the annexation of Alsace and Lorraine to Germany.

Bismarck, who had agreed to relatively lenient terms in Prussia’s recent wars against Denmark and Austria, faced pressure to enact harsher terms when it came to the war with France. Many Germans remembered centuries of French invasions. Declarations in every German state sought “that which was denied to us in 1815: an independent, united German Empire with secure frontiers.” After the stunning Prussian victory at the Battle of Sedan—a turning point in the war in which Napoleon III himself was captured, leading to the downfall of the Bonapartist regime and proclamation of the Third Republic—Wawro notes a “popular assembly in Stuttgart affirmed that Alsace and Lorraine - German until 1582 - had to be taken back to assure the land connection between north and south Germany.”

At the same time, Bismarck himself seemed to view France differently than other powers Prussia had fought. When Jules Favre, a republican statesman who helped arrange the armistice with Prussia, offered “an indemnity of several billions and a fraction of the French fleet” but without any loss of French territory, Wawro says:

Bismarck coldly rejected the offer, Favre discovering something unexpected: the usually level-headed Bismarck lost his composure when the subject was France, a country that the German chancellor held responsible for all of Germany’s miseries since the seventeenth century. Bismarck angrily reminded Favre of the successive pillage and annexations of Richelieu, Louis XIV, and Napoleon Bonaparte. France would now be forced to pay for its past arrogance and depredations.

In The Road to Verdun: World War I’s Most Momentous Battle and the Folly of Nationalism, Ian Ousby writes that “France’s helplessness to do anything about the annexation [of Alsace and Lorraine] became a fundamental axiom of the Third Republic” that viewed it as a “cruel injustice”, but one that politics as usual could not remedy. That feeling of helplessness compelled the Third Republic to look for allies, which after the death of Bismarck would lead to the forming of the Triple Entente—the Allies of World War I:

Renegotiating the peace treaty was plainly impossible, but so was taking military revenge. The war had convinced politicians that the days when it had taken virtually a pan-European alliance to defeat the first Napoléon had gone forever. France could no longer go it alone in a major European war, and above all not in a war with her newly powerful neighbour. Her task—and it would not be quickly or easily fulfilled—was to end the isolation in which defeat had left her. In the long term her security depended on understandings or alliances, even if they had to be sought in unlikely quarters, with Britain, ennemi héréditaire and colonial rival, and Russia, whom Bismarck had made an ally in the Dreikaiserbund.

Prevailing opinion in the Third Republic, Ousby says, viewed France’s loss of Alsace-Lorraine to Germany as “a wrong that would one day be righted, a wrong that would have to be righted, and such strokes of justice usually fall only to the victors in war.”

A dominant impression that emerges from reading about the harsh peace terms Prussia imposed on France in 1871 is how closely they resemble terms imposed on Germany in 1918 by the victorious Allies at the end of the First World War: annexation of Alsace-Lorraine, heavy war reparations, etc. In both cases, desire for revenge within the defeated country was a major factor in the leadup to another war to reverse the results of the last one.

Tactics: Artillery takes centre stage

One of the biggest advantages French forces had in the Franco-Prussian War was the Chassepot, a bolt-action breechloading rifle that representing the most cutting-edge military technology of the time. Prussian forces used the Dreyse needle-gun, which had been state of the art in 1866 and a contributor to their victory in the Austro-Prussian War, but was already obsolete by 1870. The Chassepot’s range far exceeded that of the needle-gun and caused massive casualties among German forces.

While superior military leadership, tactics, and training all played a role in helping Prussia overcome the advantage represented by the Chassepot, perhaps the most crucial factor was Prussia’s greater investment in artillery. The Krupp guns used by Prussian forces had far greater range than their French equivalents. Wawro writes:

[T]he tactical lessons of 1870-71 were less clear than the organizational ones. The Prussian recipe in 1866 had been simple: They had waited for Austrian infantry attacks, cut them down with rapid fire, and then briskly counter-attacked in company columns led in by swarms of skirmishers. As the Prussians closed in, their company columns subdivided into platoons and pushed into the skirmish line to envelop the enemy. Whether attacking or defending, the Prussians had made optimal use of their breech-loading Dreyse rifle, which could be loaded and fired five time more rapidly than the muzzle-loading Austrian Lorenz. After Königgrätz [decisive battle in the Austro-Prussian War, and a major Prussian victory], the defensive tactics aimed at shattering infantry attacks far downrange. In theory, the Prussians should have been stymied in 1870-71, but had won through despite the excellent French rifle and tactical discipline. How? With artillery: Cumbered with a rifle that was already obsolete in 1870, the Prussians relied almost entirely in the war on their breech-loading, steel-tubed Krupp guns, which hit farther, faster, and more accurately than France’s bronze muzzle-loaders. Indeed, the major battles of 1870-71 were decided by the Prussian artillery; the Prussian infantry attacks into the lines of Chassepots proved ineffective or even suicidal. General Julius Verdy du Vernois, a Prussian veteran of 1866 and 1870-71, said as much after [the Battle of] Gravelotte: “The improvements in firearms and the greater explosive force of the powder of the present day make it certain that the effects of firearms will be correspondingly greater [in our future wars] than it is today, when it is already sufficient … to repel any attack.”

Verdy’s predictions turned out to be accurate. In the years leading up to 1914, artillery grew ever more accurate, far-ranging, and deadly. The Encyclopedia Britannica states that artillery inflicted the greatest number of casualties and wounds in the First World War, and Stephen Bull in his book Trench: A History of Trench Warfare on the Western Front estimated that artillery caused “two-thirds of all death and injuries” on the Western Front. So great was the role of artillery in the First World War that the Canadian War Museum called it “the gunner’s war”.

War and revolution

Though it gets relatively short thrift in Wawro’s account, perhaps the most significant effect of the Franco-Prussian War was how it led to the overthrow of the rotten Bonapartist regime in France and establishment of a republic—but even more importantly, to the creation in 1871 of the Paris Commune, the first workers’ government in history. Though the Commune lasted just over two months, the experience was a watershed movement in the history of the workers’ movement and remains a rich source of lessons for revolutionaries today.

Here again we find parallels with the situation after the First World War. Just as France experienced socialist revolution in 1871 as the result of a lost war led by a reactionary dictatorship, so did Germany in 1918-19. In each case, the revolution was put down by brutal violence. The bourgeois Third Republic killed an estimated 30,000 people as it drowned the Paris Commune in blood, while far-right, proto-Nazi paramilitaries such as the Freikorps helped crush the German Revolution and murdered socialist leaders like Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht.

It’s in his descriptions of French socialists and militant workers, referred to by contemporaries as “red republicans”, that Wawro’s own class biases become apparent. What Wawro views as poor discipline by French forces and even sedition, is from a working class perspective a fantastic example of working class agitation, irreverence towards a reactionary regime, and class consciousness. Wawro cites one such instance when he describes mobilization of the Garde Mobile, a body intended to conscript all Frenchmen who had been able to evade military service:

Infected by revolutionaries, the mobiles “displayed no admiration for the virile qualities (mâles qualités) of the regular army,” which had often to be summoned to contain them, and spent most of their time disobeying orders and threatening to break out of camp to march not on Berlin, but on Paris, to overthrow the Bonapartes.

The fact that [François Certain de] Canrobert, a Marshal of France and a hero of the Crimean and Italian Wars, felt helpless to punish this bare-faced sedition, suggests the overwhelming magnitude of the problem. He could only console himself with another disbelieving letter to [Marshal Edmond] Leboeuf: “the cry ‘à Paris’ was chanted over and over in the most ignoble way, and mixed with other seditious shouts.” Overall, Canrobert judged that “good elements” in the garde mobile probably outnumbered the bad, but were helpless against the “radical agents” - les méneurs - who constantly subverted army discipline and wrung new converts from “the sluggish, uncertain, bored mass of mobiles.”

A similar example is when Wawro describes the Battle of Châteaudun in October 1871 and the army of French general Louis Jean-Baptiste d'Aurelle de Paladines, comprised of the XV Corps as well as large numbers of francs-tireurs or irregular French partisans. Aurelle’s army combined “elements of the old army, scarcely trained march battallions, and big drafts of gardes mobiles, which were now euphemistically referred to as ‘territorial divisions.’”

Wawro’s description of the gardes mobiles sounds very similar to the bourgeois media today whining about the militancy of French workers in the movement against Macron’s attacks on pensions. “Even by French standards, these territorials were breathtakingly undisciplined,” Wawro writes. “They elected their own officers - having ousted their Bonapartist ones on 4 September - and frequently refused direct orders from the war ministry or the regular army headquarters.” Electing their own officers—the horror! Sounds admirably democratic and revolutionary to me.

In the case of Germany, which appeared triumphant in 1871, dynamite had been built into the foundations of the new unified empire. Wawro quotes Karl Marx, who described the German Empire as “a military despotism cloaked in parliamentary forms with a feudal ingredient, influenced by the bourgeoisie, festooned with bureaucrats and guarded by police.” The contradictions of the new German nation-state would eventually explode in the German Revolution.