Pi (1998)

5/10

Written and directed by Darren Aronofsky in his feature debut, Pi—stylized π—has great ideas and stylistic flair but can’t quite stick the landing, which makes for a frustrating experience overall. Aronofsky, who was just 18 when he filmed the movie, deserves praise for aiming high and integrating thought-provoking concepts into an artsy Lynchian thriller on such a low budget. But after a promising first act, the film goes off the rails, becoming alternately meandering and ridiculous. Despite points for effort, it’s something of a mess.

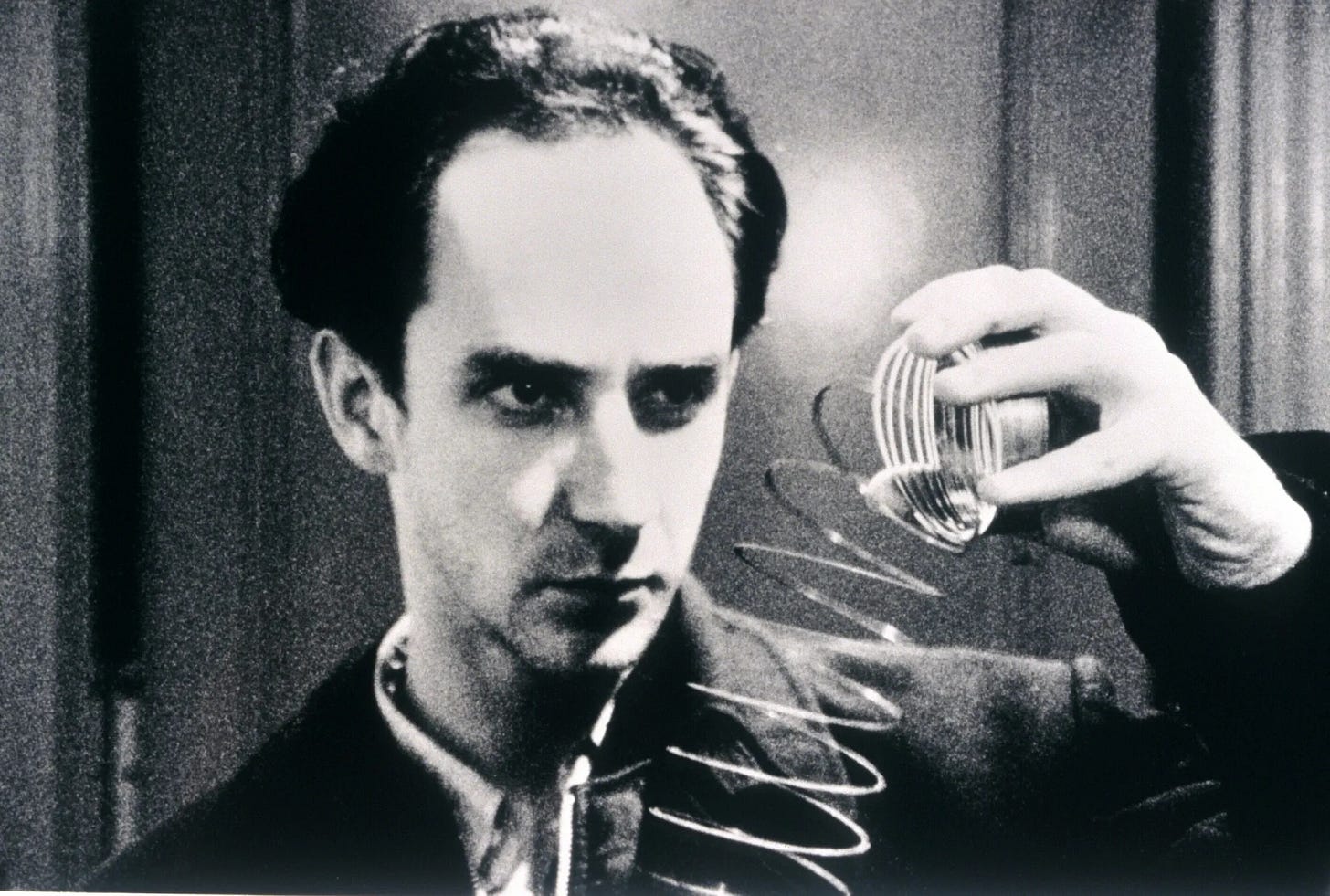

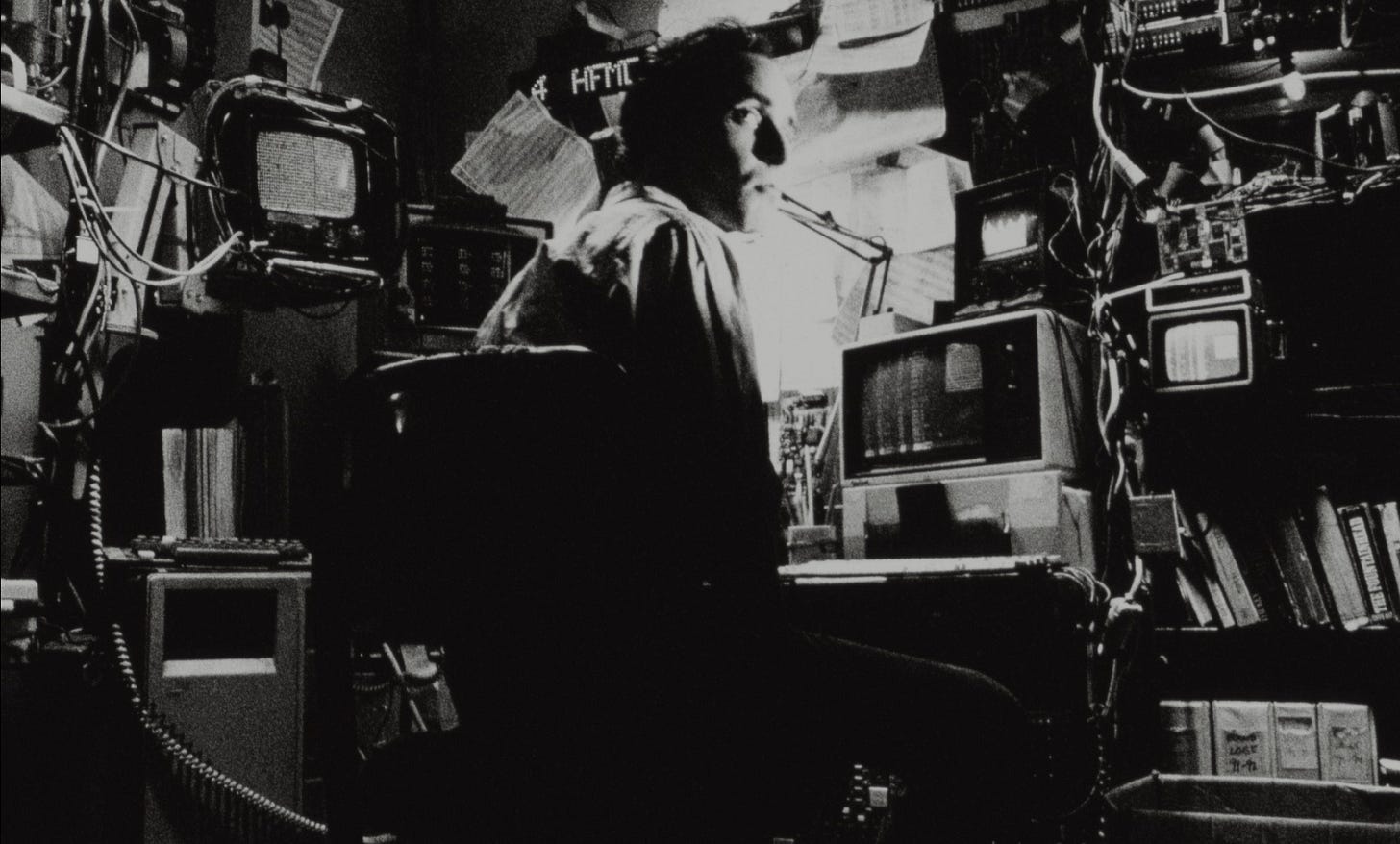

Max Cohen (Sean Gullette) is an unemployed numbers theorist suffering from worsening cluster headaches, paranoia, hallucinations, and schizoid personality disorder. Looking for patterns in the stock market, he becomes convinced he can find underlying mathematical patterns to explain all of reality. Along the way he encounters a Wall Street firm looking to use his work to manipulate the stock market, as well as Hasidic Jews who believe Max’s work might yield more spiritual rewards.

Pi starts out strong. The idea that numbers govern reality has a long history, going back to the Pythagorean mathēmatikoi in ancient Greece who were convinced that the cosmos could be understood through mathematical patterns, from basic arithmetic and musical intervals to the movements of stars and planets. Following a modern equivalent of the mathēmatikoi through his descent into madness is a brilliant starting point for a film.

The film also introduces Max, and much of the audience—this reviewer included—to Hebrew gematria, the correspondence of letters and words to numerical values. Lenny Meyer (Ben Shenkman) does mathematical research on the Torah and explains gematria to Max, along with its relation to the Kabbalah school of Jewish mysticism. Max’s quest to find perfect order in the universe through numbers subsequently acquires a spiritual bent. Religion, and Judaism in particular, is a recurring theme in Aronofsky’s films. Like Aronofsky himself, Max was raised culturally Jewish but is a non-believer, at least initially.

Aronofsky’s decision to shoot in high-contrast black-and-white reversal film gives Pi a unique look. It also fits the movie thematically, reflecting the protagonist’s headspace. Our real world is full of colours, ambiguities, disorder, while Max is obsessed with finding an underlying order in the world through numbers. Philosophically, this parallels the difference between the dialectical worldview, which views reality as contradictory and in a constant state of motion and change; and the metaphysical, which deals with fixed, unchanging categories and attempts to banish all contradiction. Max literally sees the world in black and white.

The film’s very title indicates the futility of Max’s quest to find perfect order to the cosmos through numbers. The number π, or pi, which denotes the ratio between a circle’s circumference to its diameter, is an irrational number which cannot be expressed as a ratio of two integers. While more or less equal to 3.14159, the exact value of π cannot be known. Its decimal representation is infinite and never enters into a repeating pattern. In the same way, Aronofsky suggests, there is no way to find complete order in the universe.

All these concepts make fascinating food for thought, and Aronofsky deserves praise for using them as the foundation of his first feature film. No one can fault his ambition, and he’s obviously a talented filmmaker. Whatever you can say about his work, he has a unique artistic voice, interesting ideas and stylish visuals.

But is Pi a good movie? Alas, its reach proves to exceed its grasp.

Spoilers follow.

Much of Aronofsky’s script is muddled, a problem that only gets worse as the film goes on. Characters’ actions become preposterous. Max’s computer Euclid, which he uses to make stock market predictions, prints a seemingly random 216-digit number and a single stock at one-tenth its current value. The Wall Street firm attempting to profit from Max’s work, led by Marcy Dawson (Pamela Hart), find the printout after he throws it away. Attempting to use it to manipulate the stock market, somehow they make the entire market crash. Dawson and her agents grab Max on the street and try to make him reveal the significance of the 216-digit number.

Coincidentally, at that very moment, Lenny happens to be driving by and rescues Max. Lenny takes him to a synagogue where the rabbi and his companions demand to know the number, which they say represents Shem HaMephorash, the unspeakable name of God they say will bring about the Messianic Era foretold in Jewish tradition. The idea of a conspiratorial gang of Hasidic Jews who kidnap and intimidate a mathematician demanding he give them a number feels like something out of a Mel Brooks movie. Still, it’s an interesting plot development. But Max says the number was meant for him alone and refuses to divulge it to them.

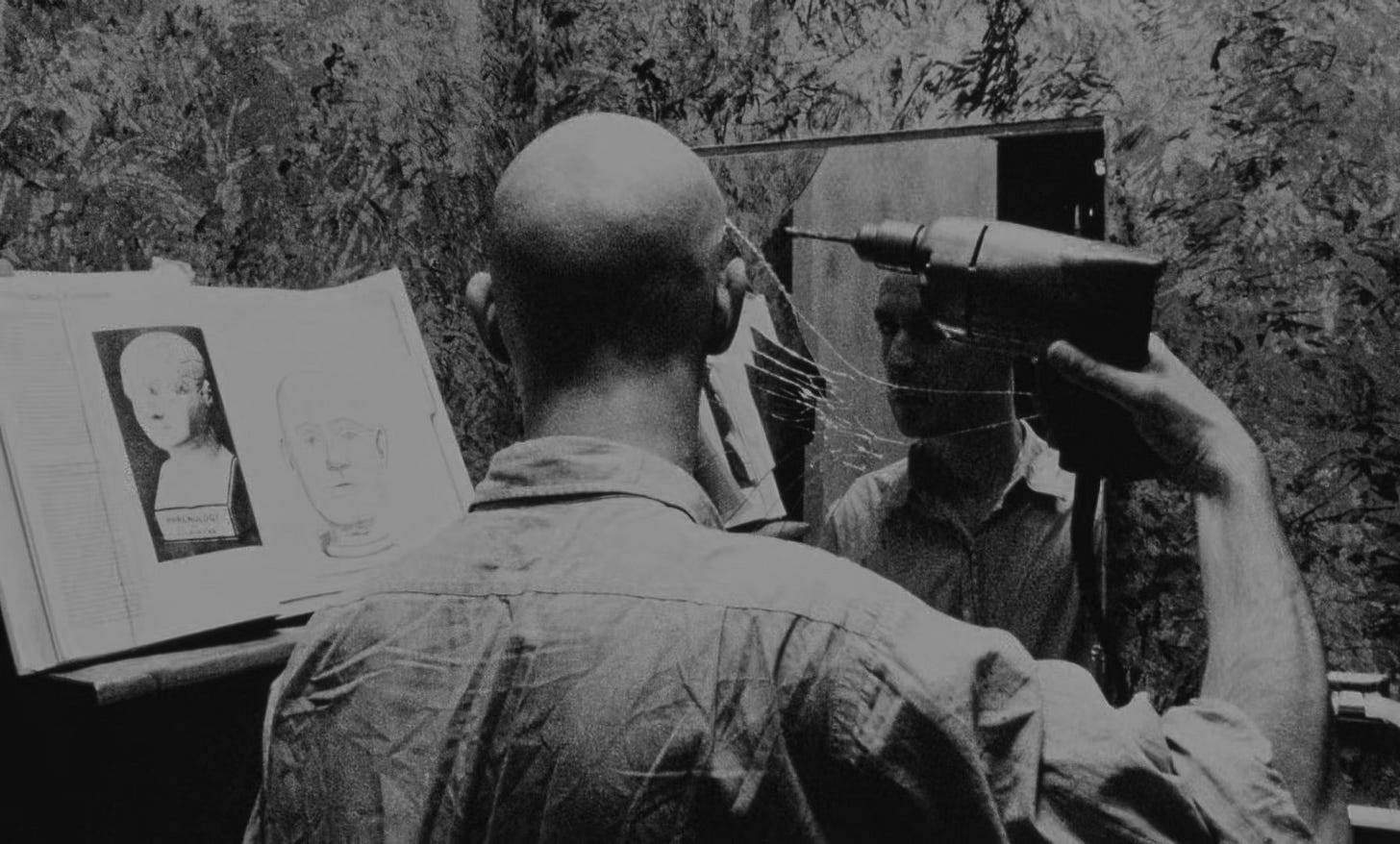

And that’s it. We don’t get any further indication what the 216-digit number represents. Maybe the whole point is that it represents nothing. Max thinks the number is linked to his headaches, tries to concentrate on it, passes out, and ends up drilling a hole in his head to try and find relief. The moment when he looks in the mirror and turns on the electric drill is more laughable than anything else.

Much of the film’s mid-section is flabby and meandering, full of try-hard artistic imagery. There’s the old man on the subway, whom Max sometimes sees before he mysteriously disappears. There’s his own doppelgänger on the subway, whom Max sometimes sees before he mysteriously disappears. Max finds a brain on the subway platform and makes an incision into it. None of this amounts to much.

The same could be said for Max’s apartment life. Aside from Jenna (Kristyn Mae-Anne Lao), a cute little girl fascinated by his ability to crunch numbers, there’s his neighbour Devi (Samia Shoaib), who appears to be attracted to Max for indiscernible reasons, given his reclusive personality and the rude way he often treats her. That relationship comes to nothing. His elderly former mathematics mentor Sol Robeson (Mark Margolis) came across the same 216-digit number years ago and urges Max to quit his work, but again, we get little payoff to that plot thread.

There are scenes of Max studying ants in his apartment. We see ants underneath the end credits, and the crew members include an “ant wrangler”. What’s the point of the ants? I don’t know. The film had lost much of its momentum by that point. One scene in the second half stands out for all the wrong reasons: a telephone incessantly ringing while Max does whatever in his apartment. We hear the sound of the phone ringing for what feels like five minutes. It’s grating and annoying.

Aesthetically, Pi is distinctively of its era. Check the opening credits, which feature driving electronic music and visuals that remind one of the zooming CGI credits in early 2000s superhero movies like X-Men, Spider-Man, and Hulk. Aided by his black-and-white cinematography, Aronofsky creates some undeniably arresting images, often just close-ups of Gullette’s face. The lead actor delivers an intense performance. None of the other actors stand out much.

If you’re looking for interesting ideas and stylish visuals, delivered by a young auteur who showed what he was capable of on a low budget, Pi is worth checking out at a reasonable 84 minutes. Unfortunately, the film’s flaws neutralize its strengths. Going in I hoped it would be one of those movies that lingered in the mind. Within an hour afterward I had to remind myself I had just watched it, which is perhaps the most devastating verdict for a film of such ambition.