The Conversation (1974)

9/10

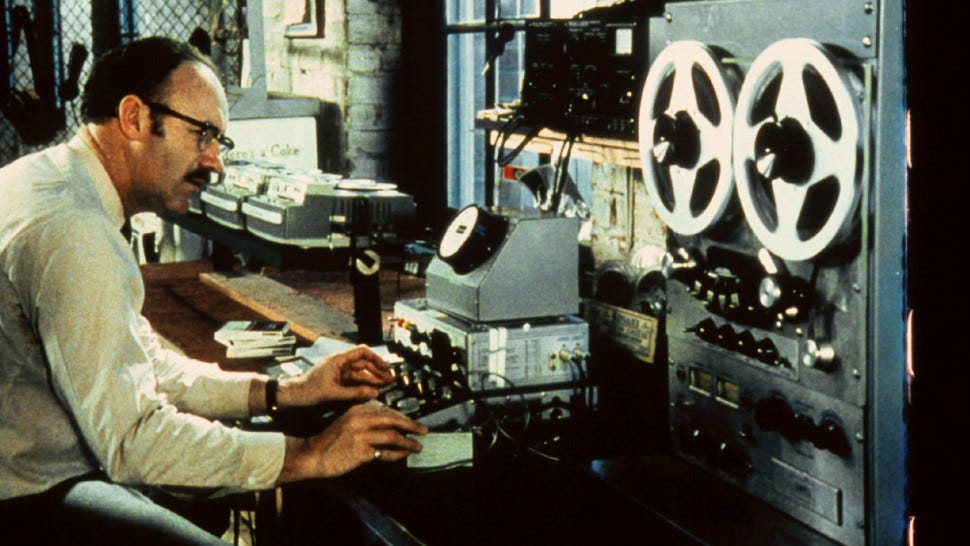

Francis Ford Coppola was firing on all cylinders in the 1970s. His four-film hot streak through The Godfather, The Conversation, The Godfather Part II and Apocalypse Now is arguably the greatest run of any director in history. Of these, The Conversation is my least favourite, but that’s purely relative, especially when you’re being compared to some of the most acclaimed films of all time. The Conversation is still a great movie—thanks primarily to an unforgettable character in Harry Caul (Gene Hackman), a paranoid surveillance expert in San Francisco who comes to believe the recording of a couple he’s been spying on reveals a potential murder.

Caul’s profession of wiretapping and eavesdropping on others fuels his intensely private nature. Coppola, who also wrote and produced the film, establishes the character’s paranoia when we see Caul at home, where he has three locks and an alarm on his door. He breaks up with his girlfriend Amy (Teri Garr) on his birthday after she asks him what he feels are too many questions, and says he has a certain way of opening the door. Like many protagonists in 1970s films by Coppola and Martin Scorsese, Caul is Roman Catholic and troubled by guilt, in this case over a past surveillance job that led to the deaths of three people.

Yet as we see, Caul is right to be paranoid. After attending a surveillance convention and having drinks with company that includes professional rival Bernie Moran (Allen Garfield), Caul uncharacteristically brings the alcohol-fueled party back to his workshop. He and former assistant Stan Ross (John Cazale) share details about the current case they had been working on and Caul sleeps with Meredith (Elizabeth MacRae). The next morning, he wakes up to find Meredith gone and his tapes stolen. Martin Stett (Harrison Ford), the assistant of his client known only as “the Director” (Robert Duvall), tells Caul they have the tapes and to bring the photographs he has taken of the couple. Subsequent events and the resolution of the case go in unexpected directions.

Hackman delivers an excellent performance. Working from Coppola’s screenplay, he creates a very different character to his “Popeye” Doyle in The French Connection. Where Doyle was boisterous and aggressive, Caul is introverted, bookish and secretive. But the subdued rage boiling under the surface of this character explodes in a memorable scene where Caul tears apart his entire apartment looking for bugs after Stett offers irrefutable proof that they’re watching him. Unable to find the bug, Caul plays his saxophone amidst the rubble, a powerful image that conveys how his chosen vocation has destroyed his personal life.

Through its insight into the surveillance of the 1970s, The Conversation provokes wonder at how much this technology has advanced in the decades since. Coppola said in his DVD commentary that he was shocked to learn his film used the same surveillance and wiretapping technology the Nixon administration used to spy on political opponents prior to the Watergate scandal. While Coppola had completed his script for The Conversation by the mid-1960s, the film was released a few months before Nixon’s resignation, leading many viewers to incorrectly view it as a response to Watergate.

The Conversation is a thoughtful film very much attuned to the spirit of the time in which it was made. Its story offers a compelling mystery, anchored by great performances and a terrific jazzy piano score by David Shire. Though there are some meandering sections, overall this is a solid example of downbeat ’70s cinema.