The Passion of the Christ Revisited

After meaning to do so for a few years now, I finally rewatched The Passion of the Christ for Good Friday. I first caught Mel Gibson’s magnum opus not long after it came out in 2004, though I didn’t watch it in theatres. Everyone seemed to agree on one thing: this is an extremely violent film. Roger Ebert called it “the most violent film I have ever seen”. Beyond that, reactions ran the gamut from those who described it as a transcendent religious experience to those who considered it a virulent antisemitic hate film.

Watching it again years later, I found that my reaction to the film was much the same as before, but intensified. Those who find the movie repellent have good reason to. The violence is excruciating and non-stop. The depiction of Jews in the film is exactly what one might expect from a director with ultra-reactionary political views who comes from a traditionalist Catholic sect that rejects Vatican II, and who is notorious for his alcohol-fueled racist and antisemitic rants.

To be fair to Gibson, one can argue that his film (though it drew upon other sources) is accurate to what is in the gospels. The sympathetic depiction of Pontius Pilate is not new and if anything highlights how politicized the writings of the gospels were. Early Christians were anxious not to antagonize the Romans. But it's hard to imagine a governor in an empire built on slavery, which crucified thousands of slaves who dared to revolt under the leadership of Spartacus, literally washing his hands to absolve himself of responsibility for executing a convicted criminal from an oppressed people. If this has become the focal point for an antisemitic canard that has lasted for nearly 2,000 years, this is less Gibson’s fault than those of the gospel writers.

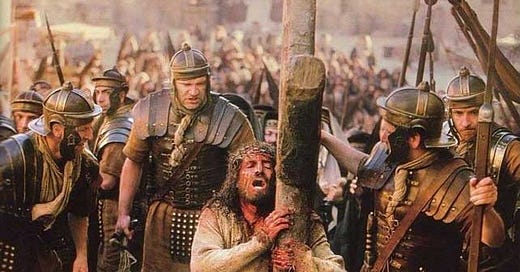

As for the violence, film critic David Edelstein amusingly dubbed the film The Jesus Chainsaw Massacre at the time of its release. The gruesome, detailed portrayal of Christ’s torture and execution leave nothing to the imagination. It goes on and on and on. For much of the film, Jim Caviezel, the actor who plays Jesus, does little other than moan and scream in agony, buried under makeup to show him scourged and beaten to a bloody pulp.

Defending the film, which he rated 4 out of 4 stars, Ebert had this to say:

What Gibson has provided for me, for the first time in my life, is a visceral idea of what the Passion consisted of. That his film is superficial in terms of the surrounding message—that we get only a few passing references to the teachings of Jesus—is, I suppose, not the point. This is not a sermon or a homily, but a visualization of the central event in the Christian religion. Take it or leave it.

Fair enough, and I can’t disagree with Ebert’s take here. Even so, it’s hard to deny that the endless violence is excessive. At a certain point, Gibson arguably goes beyond “visualizing the central event in the Christian religion” and begins to offer a window into his own unique mind.

The Passion of the Christ makes a strong case for the auteur theory of cinema, in which the director is the “author” of a film. Gibson spent $30 million of his own money to make this film and distributed it himself. While he made changes here and there (initially, for example, he did not want subtitles for the dialogue), it seems clear that by and large this is the film Gibson wanted to make. And it is an intensely personal film. Though I agree with Ebert that the basic point is to visualize the story of Christ’s Passion, this is very much Gibson’s Passion. That is to say, it is the story of Christ’s death and execution as filtered through the very unique perspective of Mel Gibson.

Throughout his career as an actor and director, Gibson has shown a few consistent threads. His characters have a knack for being tortured, often in martyr-like fashion. When William Wallace is drawn and quartered in Braveheart, managing to yell out one last call for freedom before he dies, it feels like a dry run for The Passion of the Christ. Focusing so much on the torture and execution of Jesus also allows Gibson to portray the extreme violence that is another hallmark of his work.

The way Jesus is portrayed by Gibson gives a nagging feeling that this is is the work of someone with sadomasochistic tendencies and a severe persecution complex. “If the world hated you, be aware that it hated me before it hated you,” Jesus says. The Passion of the Christ came out before Gibson’s DUI arrest and antisemitic remarks that cast him out of polite company in Hollywood (at least for a while), but it certainly comes off like the work of a man who feels hated. The Jews in the film rant and rave calling for Jesus’ death, the Roman soldiers whip and scourge and spit at Jesus to such an extent that one begins to lose their suspension of disbelief.

One of the better arguments I’ve heard for the excessive violence is that modern audiences are so desensitized that this approach is necessary in order for them to get the message. Gibson says he wanted to underscore “the enormity of the sacrifice”. The violence goes on so long in such grisly fashion that the audience begins to feel like it too is being tortured. Maybe that’s the point.

A lot of characters in this movie feel fairly one-dimensional. But if one is to take Ebert’s “visualization” perspective, this isn’t a film that is meant to feature deep and complex characters, though Jesus and Pilate each have powerful moments of self-doubt. This movie is designed as an “experience” in the same way that 2001: A Space Odyssey was an experience. If anything, the characters in 2001 were much more flat and one-dimensional than those in The Passion of the Christ.

The power of this film comes from its total commitment to the religious events it portrays. Jesus as Saviour, his violent torture and execution for the sins of humanity, his ability to work miracles, the depiction of Satan as a literal being, the existence of heaven and hell, the biblically accurate portrayal of figures like Caiaphas, Pilate, Judas, Mary, Peter, etc.—the film accepts them all completely. To paraphrase what Ebert expressed so eloquently, either you buy into this or you don’t.

By the time the credits rolled, I felt exhausted. But I also felt that I had been given just enough glimpses of Jesus’ life and ministry that the dramatic effort of his death and brief glimpse of his resurrection had the intended cathartic effect. By the end, for better or for worse, I indeed felt like I had had an experience, which is not something you can say about all films.

I’d be interested in seeing a film that exhibits this level of commitment depicting other key events in Christianity and other religions. Considering the importance of religion in human history and culture, I respect the work of a director who is willing to go all-out in presenting a literal view of his faith. Unlike so much Hollywood product, this feels like a strong personal and artistic statement. It is full of compelling imagery, in part due to how much those images have become ingrained in our collective consciousness and remain so even in this secular age. To me that’s a film that, for all its problems and controversy (or perhaps because of them), is still worth a look.